Motion Is Yet to Come

Tali Ben-Nun

“The zero of form,” said Malevich about the black square that he had painted on a white background, on a square canvas (Black Square, 1915, oil on canvas, 79.5 x 79.5 cm). The empty square is “everything.” The empty square is “nothing.” It has an object or does not. It describes a reality or obscures it. Is the black on the white, or vice versa? What is the relationship between finite and infinite, and where does the boundary go, if there is one?

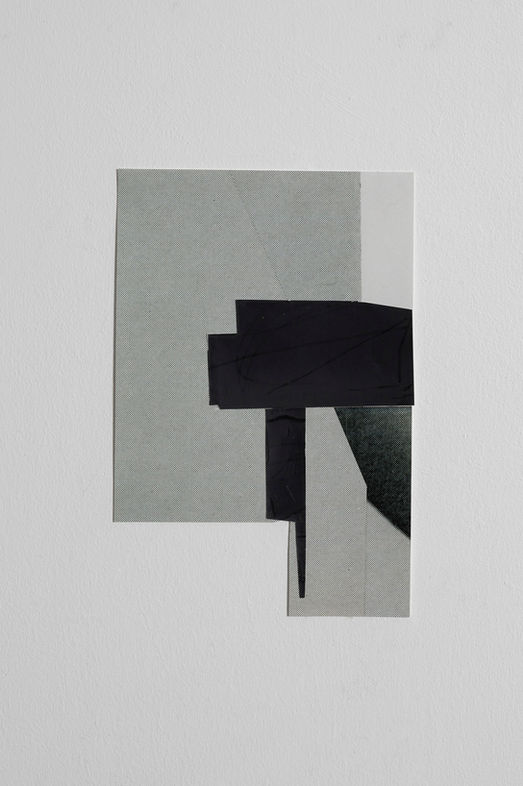

In her current exhibition, Tali Benbassat presents large-scale prints alongside tiny collages. The works are based on cut-outs of abstract shapes – geometric or organic – which she folds, replicates, disassembles, and reconstructs. As in a modular origami game, she creates symmetrical and asymmetrical compositions that are harmonious or disharmonious, and in all of them it seems that the composition is not the essence, but a means through which motion takes place. The building blocks of the image fall apart and drain it of narrative meaning. The spaces elude characterization and identification; faced with the gaping questions, with the white and the black, Benbassat repeatedly positions herself at her own zero point.

In 2001, at the Office in Tel Aviv Gallery, Benbassat presented a series of office interiors, bare and empty of people, inside large-scale minimalist light boxes. The images, which had been taken from design magazines, had been scanned, processed, and repainted on a computer: a kitchenette, work areas, a conference room, a lecture hall, office furniture, and devices such as a printer, computer, and projector, were all given the same color treatment of black-white-and-gray – with the exception of an empty lecture hall, whose chairs were painted bright red. Through these digital renderings of workspaces, and her treatment of geometric surfaces (wall or table) and partitions between interior and exterior, Benbassat formulated a compact language based on restraint and concealment and underlain by rigid grids. The near-realistic scale of the interior spaces, coupled with the stark contrast between flatness and the illusion of depth, made the collages illuminated by the cold neon light look bare and sterile.

In 2003, Benbassat presented a series of photographs of sculptures at the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art titled Modular Space, consisting of magnified models of imaginary spaces that she had placed, as though frozen or petrified, in lightboxes. The function of the spaces (living, storage, work, sports, waiting, or leisure) remained obscure, creating a mixture of closeness, alienation, and bewilderment.

In hindsight, the two series appear to have been harbingers of what was to follow. The process of abstracting the interior spaces and emptying them of human cues, the use of black-white-and-gray hues, and the digital processing prefigured the present set of prints and collages. However, the rigidity, emptiness, and polished meticulousness are now replaced by a more relaxed aesthetic approach that allows the artworks’ support, technique, and work processes to be present in the works themselves and to take part in them.

The print functions both as an autonomous element and as a reproducible piece in a jigsaw puzzle. The black background becomes a space in which various elements confront each other: feminine, patchy, harmonious, masculine, linear, disharmonious, and so forth. The black pigment is opaque, dense, and absorbed into the paper fibers; the white is transparent, and vestiges of the process are etched upon it. In the encounter between the contrasts we see glimpses of the gray, which gives the compositions a three-dimensional appearance and creates volumetric shadows. Within the solidity and opacity of the black or the effusive transparency of the white, the gray is present as the generator of motion, as the element that elevates the plane.

The printing task is carried out slowly, comprising a continuous sequence of actions in a structured order. At the same time, it has an element of uncertainty, with surprises that occur in the process and require a spontaneous response. The entire body is active during the printing, and one can almost sense the movement and the physical weight imbued in the metal plates. The pressure exerted by the press, the cutting marks, the imprint of the shapes on the plate, the placement, the shifting, the pressing, the drying, and the mistakes, as well – all are evident, in a kind of subtle game of revelation and concealment.

The collage works can (also) be read as a metaphor of fusion. Benbassat’s studio is situated in the heart of a dusty and noisy industrial area. The subcutaneous layers of the urban grid, the intense Israeli light, the dust and the soot rising from the street, permeate the works in a kind of slow motion. The chaos, fracturing, and fragmentations that emanate from the urban experience are given plastic expression. The cracks, the loose connections, the congruencies and doubts remain bare and visible within the works, like the outline of a soul.

Print and collage lie somewhere between painting and photography – two dominant art forms in Benbassat’s oeuvre. They bring together the one-off, manual action of painting with the replication, variations, and manipulations enabled by photography; the geometric dream of the Suprematists with the mechanical-urban movement of the Futurists; the universal, homogeneous, and uniform order and rationale that the Bauhaus style sought to establish, with the disorder, randomness, and non-sense of Dada.

The monumental print and the miniature collage expand each other. Without a subject, and with monotonous monochromaticity, they make up compositions with no distinct core. With no center of gravity. They can be hung in all sorts of ways, much as one can view them from any angle that the eye fancies. The freedom, chaos, and movements of the artist’s working body are embedded in the works. Forward and backward, inward and outward, toward the past and toward the future, in front of and facing the viewers – they contain and hold a relentless state of motion.

And perhaps this is nothing but a semblance of a long-awaited motion – a motion yet to come.

* The name of the exhibition is a quotation from a poem by Maya Bejerano, “Manuscript of a Dancer, or Choreography of the Soul,” from the volume Waking at the Heart of the Diagonal (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 2009), p. 8 (in Hebrew), with the poet’s permission.